The concept of a jury of one’s peers dates back to the Magna Carta in 1215. Clause 39 of the Magna Carta reads:

No free man is to be arrested, or imprisoned, or disseised, or outlawed, or exiled, or in any other way ruined, nor will we go against him or send against him, except by the lawful judgment of his peers or by the law of the land.

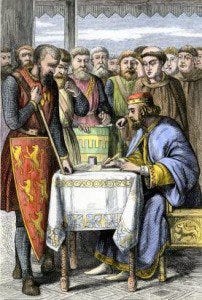

This is one of the few clauses of the Magna Carta that is still in legal force. Recall that King John was essentially backed into a corner and had to seal the Magna Carta to avoid a battle at Runnymede with barons who were sick of his wasteful ways being funded by demanding more and more of their wealth.

At that time, the idea of a jury of peers was so that free men would not be judged by those outside of their social class. Nobility would be judged by equally ranked nobility, commoner by equal status commoners, and so on.

At a time when England was ruled by a man who was fond of saying that “the law is in my mouth,” meaning the law was whatever he said it was, this prevented King John from arbitrarily punishing those who did not comply with his edicts. More details can be found in Chapter Thirty-Nine of Magna Carta: A Commentary on the Great Charter of King John by William Sharp McKechnie.

Fast forward to colonial America. English citizens living in the colonies maintained that their rights while living in the colonies were the same as the rights afforded to English citizens living in England. The Crown did not agree. Consequently, colonists wound up with a long list of complaints that were ultimately outlined in the Declaration of Independence.

Its list of grievances read in part and in this order:

For imposing Taxes on us without our Consent:

For depriving us in many cases, of the benefits of Trial by Jury:

For transporting us beyond Seas to be tried for pretended offences

These three grievances tell a story. Much as the barons did in the time of the Magna Carta, English colonists in America objected to the confiscation of their wealth without having any say in the matter. While the Magna Carta sought to remedy this in part in Clause 39, colonists were incensed that they were not afforded equal protection by the processes that had evolved out of this Clause as those overseas enjoyed.

To thwart colonial jurors’ ability to protect their law-breaking, tax-protesting neighbors by exercising their right to jury nullification in local trials by juries of their peers, the English government took steps to circumvent them. One such step was a plan to remove such trials to be heard in Admiralty Courts far from where the alleged offenses took place. Because Admiralty Courts did not provide for juries and had the judge decide the facts as well as the law in each case, no sympathetic jurors would stand in the way of conviction.

It is no wonder, then, that the early United States government drew heavily on the Magna Carta and other English legal history and scholarship when the Revolution was in part to reclaim the rights the colonists had asserted as English citizens. The language from the Magna Carta referring to a jury of one’s peers appears not only in the Sixth Amendment to the United States Constitution but also in the constitutions of several states.

The modern United States does not, however, have the class-based social structure that was in place overseas at the time of the Magna Carta. What, then, does this mean now in the United States’ legal system?

The Supreme Court of the United States explicitly addressed this in Strauder v. West Virginia (1880). In this case, the Court overturned state provisions for excluding from juries black citizens, whose legal status was explicitly made legal to white citizens’ legal status by the 13th, 14th, and 15th Amendments, noting:

The very idea of a jury is that it is a body of men composed of the peers or equals of the person whose rights it is selected or summoned to determine; that is, of persons having the same legal status in society as that which he holds.

and

The right to a trial by jury is guaranteed to every citizen of West Virginia by the Constitution of that State, and the constitution of juries is a very essential part of the protection such a mode of trial is intended to secure. The very idea of a jury is a body of men composed of the peers or equals of the person whose rights it is selected or summoned to determine -- that is, of his neighbors, fellows, associates, persons having the same legal status in society as that which he holds.

The Court further cited the language of Strauder v. West Virginia regarding peers in addressing the exclusion of women from juries in its ruling in Taylor v. Louisiana (1974). Consistent with the earlier ruling in Strauder v. West Virginia, the Court ruled that:

The requirement that a petit jury be selected from a representative cross-section of the community, which is fundamental to the jury trial guaranteed by the Sixth Amendment, is violated by the systematic exclusion of women from jury panels, which in the judicial district here involved amounted to 53% of the citizens eligible for jury service.

The practical result of these rulings is this: a jury of one’s peers is one that is drawn from a fair cross-section of the people who have the same legal status in society as the accused.

Individual juries do not have to have exactly the same representation by race, gender, and other factors as the community in which the offense was allegedly committed. However, in order to ensure that a jury meets the current legal standard for a jury of peers, the pool from which its jurors are drawn must be a reasonably representative cross-section of the community. What that specifically means is a matter of ongoing litigation in the courts today.